Organizational Structures & Influences according to PMBOK® Guide – Sixth Edition

28 April 2020Organizational Structures & Influences according to PMBOK® Guide – Sixth Edition

Even when working with the most independent project team, it’s important to remember that projects still take place within larger organizations and structures. Our project work needs to align with an organization’s goals, their expectations, policies they may have, as well as any practices that they may maintain in the ways that they go about doing their work.

It should be expected that our project team and its work will largely conform to the values of our organization as a whole. If, for example, our organization is not very tolerant of risk, then we should expect risk management to be an area of emphasis for us in our project planning purposes. Similarly, if we pride ourselves on the quality of the products that we develop, then we should expect quality management to take a prominent role within our project planning, as well.

Three different organizational components that can influence the way we go about managing our project’s work include an organization’s culture, the style, and the way that it goes about its work, as well as the organization’s formal structure.

This includes, but is not limited to the organization’s project management style, which may differ somewhat, and is separate from the organization’s overall style or structure. Whether your organization uses project management offices, program management, portfolio management, or some combination thereof, in order to better manage its many different projects, we also need to consider an organization’s culture and structure at large as part of the way we go about designing our project’s work.

External factors can also make an impact on the way we go about our projects. Our relationships with any clients, joint venture partners we may be working with, or other types of partnerships might necessitate us conforming to different structures in the way we approach our project than we might otherwise do.

For example, if we’re completing work for a client, we may ideally prefer to not have a certain component of our project’s work completed until later in the schedule, because we find it to be more efficient. We believe that it might be in the project’s best interests and so on.

But what really matters is what the client thinks in this regard. And so, if having a certain component complete is necessary for us to pass a vital milestone as part of our agreement with the client, we need to structure our project’s work accordingly.

Organizational structures can affect how projects develop and progress, how our resources are allocated, as well as how resources are made available for project work to take place.

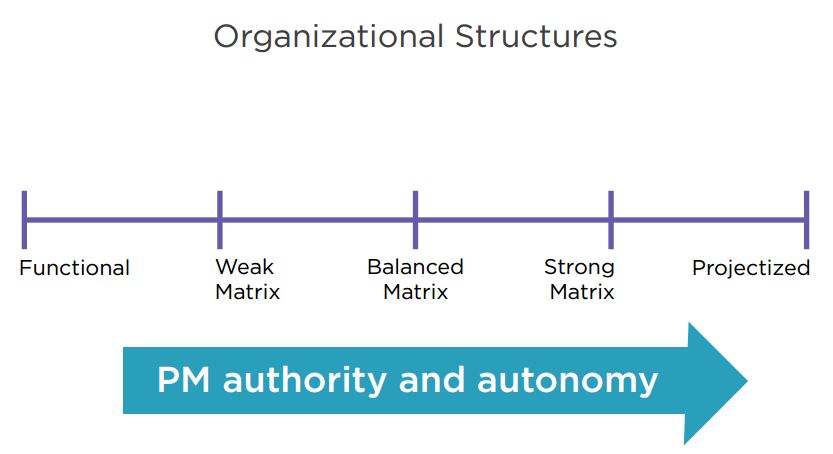

Generally speaking, organizational structures can be found on a continuum, ranging from purely functional to purely projectized in nature. The farther we go on this spectrum from left to right, the greater a project manager’s authority and level of autonomy will be in their decision making.

In a purely functional organization, the organizational chart will likely look something like this, with a CEO with number of direct reports, each looking over a functional area of the company, be it finance, engineering, legal, and so on. Underneath each of these top line lieutenants, we would have a variety of other staff.

Of course, additional levels of complexity could exist here, as well, but we would find an organizational chart generally conforming to this structure. In this case, project coordination would typically take place at a functional manager level, where the functional managers serve as the conduit between various staff that have different talents to offer to the project team.

In a functional organization structure, project managers tend to have little to no formal authority, and their control over resources is also rather minimal. From a budget control standpoint, the functional managers are the ones that would hold the keys. In this case, the project manager may act more like a coordinator working to rally resources together, but without the formal authority necessary to actively direct work.

In a projectized organization, this is different. We see that underneath the CEO, there are a variety of different project managers focused on accomplishing specific tasks for the organization. Each of their staffs may have all of the talent necessary in order to complete their objectives. As such, project coordination would take place within each of these different project team cells, rather than across the top line board of several different key executives.

In the fully projectized organization, the level of authority that a project manager has to bring to bear is high to total in nature. Their control over resources similarly is extremely high. And they are directly responsible for the control of both budget, as well as schedule, and other components, rather than answering to a functional manager of some sort. It’s rare to find organizations that purely conform to either a functional or a projectized nature.

Rather, most organizations fall into what we call a matrix blend, where functional and projectized structures come together at some level. The precise structure will vary based on the relative influence of project managers and of project initiatives in general, versus that of functional managers within the organization, across the same sort of spectrum we saw earlier.

There are three different types of matrix structures we refer to, weak matrix, balanced matrix, and strong matrix.

In the case of weak matrix organizations, project managers hold little power over personnel. Although, they may have more than any purely functional organization. Still, their work is more akin to that of an expeditor or coordinator, rather than a manager who can lead and direct their team explicitly.

Weak matrix organizations are situations where project managers will find themselves unable to make or enforce many project decisions individually. And as such, it’s of particular importance for project managers to work with others, negotiate, and to help them see how the project can be a benefit to them and their division within the company.

In the case of balanced matrix organizations, authority is, well, balanced between the project and functional managers. Project managers typically focus on the project full-time, but their resources often will not. Split up across several different projects, or perhaps lending a few hours here and there to project work while continuing to exercise day-to-day operational duties.

In a strong matrix organization, the project manager holds most control and has budgetary authority. And further, they may select staff directly or in conjunction with functional managers. In a strong matrix, projects managers have broad authority over resources and utilization, but it may not be complete.

For example, an organization where a project manager has the authority to decide the number of staff that they need, but the authority to assign specific staff still lies with the functional manager, would still be considered a strong matrix organization.

As detailed above said, few organizations are purely functional or projectized in nature. And organizational structure may even appear to vary at different levels of the organization.

There are plenty of stories of large companies where a small skunkworks team working under the radar was able to accomplish great things in part because they were outside of the typical norms and structure of that organization.

However, if we were to look higher up within that same organization, we might find it more difficult for work to continue. Just the same, within some organizations, we might find that only at that higher level do we have the discretion and authority necessary to do things differently than might happen elsewhere in the organization.

Some of the key factors to keep in mind when it comes to a project and organizational structure are the strategic importance of the project to the business overall.

The more important the project is, the more likely the project manager is to be infused with the authority to make changes, or to buck the norms as we see them within the organization or company.

The ability of stakeholders to influence the project is also important. If key stakeholders outside of the project sponsor still have the ability to control resources, that diminishes the authority and purview of the project manager.

The degree of organizational project management maturity is also important. In some companies, you may have project management offices, program management initiatives, or even portfolio management taking place where there are some strict guidelines in place about how projects are managed within the organization.

In other more organic or newer companies, we might find that there simply is no precedent for the project we’re undertaking in the company’s past work. As such, we may very well be the project team that helps to generate some of those assets, those policies and procedures that could then later guide future project work.

The project management systems that we have to rely upon can also have an impact here, depending on the sophistication both from a tool standpoint and from a policy standpoint of what project management systems we have in place.

Additionally, organizational communication tools and techniques can also come into play. Additional factors include a project manager’s level of formal authority, as explicitly listed by either the project sponsor, project management office, or other key executives within the organization who have the ability to define this role.

Resource availability and accountability can matter here, as well. If, for example, a project manager might require certain resources but they simply don’t exist within the organization, their power to actually do something about this is relatively low unless they also have the power to hire from the outside.

Similarly, if the project manager is unable to remove members who are unproductive from the project team, then they lack the ability to hold project team members accountable to a full extent within the project.

Control of project budget might reside with the project manager directly, with the project sponsor, or be directly overseen by a project management office. Depending on where this buck stops, project managers may have more or less authority when it comes to budget related issues.

The overall role of the project manager should also be considered, as should the composition of the team and allocation of project resources.

Regardless of what your organization chart might formally say, understanding where strategic resource and budgetary authority lie is key to your role as a project manager, and how you can best meet project objectives.