The long history of the paved highway

30 July 2019The long history of the paved highway

It is impossible to know where or when the wheel was invented. It is hard to imagine that Stone Age humans failed to notice that circular objects such as sections of tree trunk rolled.

The great megalithic tombs of the third millennium BC bear witness to ancient humans’ ability to move massive stones, and most commentators assume that tree trunks were used as rollers; not quite a wheel but a similar principle!

However, it is known for certain that the domestication of the horse in southern Russia or the Ukraine in about 4000 BC was followed not long afterwards by the development of the cart.

It is also known that the great cities of Egypt and Iraq had, by the late third millennium BC, reached a stage where pavements were needed. Stone slabs on a rubble base made an excellent and long-lasting pavement surface suitable for both pedestrian usage and also traffic from donkeys, camels, horses, carts and, by the late second millennium BC, chariots.

Numerous examples survive from Roman times of such slabbed pavements, often showing the wear of tens of thousands of iron-rimmed wheels. Traffic levels could be such that the pavement had a finite life.

Even in such ancient times, engineers had the option to use more than simply stones if they so chose – but only if they could justify the cost! Concrete technology made significant strides during the centuries of Roman rule and was an important element in the structural engineer’s thinking.

Similarly, bitumen had been used for thousands of years in Iraq as asphalt mortar in building construction. Yet neither concrete nor asphalt was used by pavement engineers in ancient times, for the excellent reason that neither material came into the cheap, high-volume category. As far as the pavement engineer was concerned, economics dictated that the industry had to remain firmly in the Stone Age.

Even in the days of Thomas Telford and John Loudon Macadam – the fathers of modern road building in the UK – the art of pavement construction consisted purely of optimising stone placement and the size fractions used.

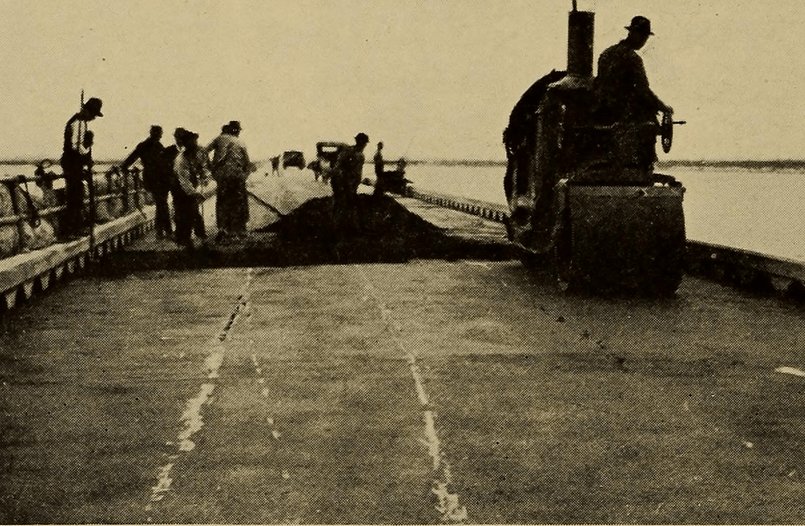

Times havemoved on; themassive exploitation of oil has meant that bitumen, a by-product from refining heavy crude oil, is now much more widely available. Cement technology has progressed to the stage where it is sufficiently cheaply available to be considered in pavement construction. However, there is no way that pavement engineers can contemplate using some of the twenty-first century’s more expensive materials – or, at least, they can be used only in very small amounts. Steel can only be afforded as reinforcement in concrete and, even in suchmodest quantities, it represents a significant proportion of the overall cost.

Plastics find a use in certain types of reinforcement product; polymers can be used to enhance bitumen properties; but always the driving force is cost, which means that, whether we like it or not, Stone Age materials still predominate.