World’s Biggest Infrastructure Project is One You Never Heard Of

6 July 2018Table of Contents

World’s Biggest Infrastructure Project is One You Never Heard Of

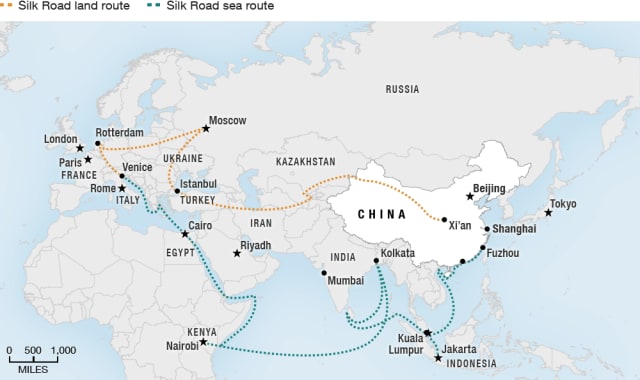

While the U.S. dawdles with much needed domestic infrastructure upgrades, China is already engaged in a project so massive that it will tilt the Earth in its favor. The trillion-dollar Belt Road Initiative (BRI) is a plan for a web of transportation routes (road, rail, shipping lanes, more—all leading to China) that will be created or expanded over the next 30-plus years. The BRI’s main purpose is to facilitate trade. China, the world’s leading producer of exports, no longer wants to rely on slow moving boats to move its goods out.

Lost in Translation

BRI not ringing any bells? This development plan for a number of megaprojects was introduced in 2013 as the One Belt One Road (OBOR). The “belt” referred to the roads, and “road,” inexplicably, the sea lanes. It was renamed the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) at the 2017 Belt and Road Forum(BARF? Really, guys?) in Beijing.

The U.S.—and most of the West—paid scant attention. Even now, as money and concrete are pouring into projects, the U.S. continues to draw inward, led with an “America First” ideology. By the time the concrete is dry on the New Silk Road projects (China hopes to finish by 2049), the economic effect and, later, its political and even military consequences of the New Silk Road could make China the most dominant world super power for centuries to come.

Walls and Bridges

Under the Trump administration, the U.S. pulled out of the Paris Climate Accord in 2017 and then the Trans-Pacific Partnership. The proposed Mexico border wall extension will further separate the U.S. from neighbors to the South.

China’s state-run news agency responded with this during the Beijing conference, without any sense of irony: “As some Western countries move backwards by erecting ‘walls’, China is contriving to build bridges.” It was China that built the most famous wall of all time, the Great Wall, to keep out its neighbors to the North.

The New Silk Road will help China connect its far-flung provinces, but most of the development plans seem to be in neighboring countries with global trade partners. The BRI will help connect the heavily populated eastern part of the country with its Western provinces, which are considered underpopulated and underdeveloped. The highly promoted two thousand-kilometer Qinhai-Tibet railway, ostensibly built for tourism, deposits 3,000 Han Chinese (the predominant Chinese ethnic group) into Tibet, and has already made native Tibetans a minority in their own land.

While China has earmarked $900 billion to spend on the New Silk Road, the country is also prepared to loan $8 trillion to over 60 countries, many of them too poor to fund their own big infrastructure projects. One trillion dollars is said to have already been allocated by these countries. By comparison, the entire 47,000 miles of the US Interstate Highway system cost roughly half that amount ($459 billion).

Bugs Life Leads to Silk Roads

On its way to adulthood, the larvae of a certain insect, the Bombyx mori, gorge themselves on mulberry leaves and spin themselves into a cocoon so they can privately morph into an adult moth. One of these journeys was interrupted thousands of years ago, as Chinese legend has it, when a cocoon fell from a tree into a royal tea cup. A bored, but inquisitive, queen unraveled the cocoon into a one surprisingly long continuous fiber. The fiber could be spun into a thread which could produce the most luxuriant fabric. A silk industry was born.

Word of silk spread all the way to ancient Rome. Favored by Roman nobility, its trade became lucrative. Centuries of trade between Asia and Europe led to a tangle of trail and thoroughfares. Countless travelers, traders and pack animals demanded food, shelter and supplies. Marco Polo travelled along the Silk Road in the 13th century. Towns and cities formed and grew. The Silk Road also spread wealth and facilitated cultural exchange.

The journeys along the Silk Road were not for the faint-hearted. They were plagued by bandits, extortionary rates of passage, ridiculous extremes in weather and imposing physical barriers. Some dangers were unseen. The camels carried fleas and introduced the bubonic plague to Europe.

The Silk Road name came much later, coined by German geographer Ferdinand von Richthofen in 1877 who was seeking a succinct term for the multitude of thoroughfares connecting Asia and Europe. Historians now favor the use of the more accurate “Silk Routes.”

Slow Boats to China

The Middle Ages led to ocean-going ships that took over from camel caravans over deserts and mountains. The Silk Road lapsed to serving local trade.

The modern maritime fleet relies on container ships for dry goods and tankers for liquids, both of which have reached gargantuan proportions. The biggest of all ships, a tanker, holds enough oil for 15,000 tanker trucks. Only a bit shorter, the biggest container ship carries 19,000 truck loads. Since China houses the world’s biggest labor force and produces the most goods, it makes sense that China also has the largest set of container ports to get those goods out, including the world’s biggest in Shanghai.

It’s not enough. The world’s growing appetites for goods demand that more of them arrive faster. Those ships could use more ports, and existing ports could be modernized. More ships could be built. For goods that are to be consumed and producers on the same landmass, why not connect them with modern highways and railroads? Why go around continents or through choke points (examples: the Suez and Panama canals) when you can make a relative beeline with a tractor trailer on a smooth multilane highway?

|

|

|

|

Maritime traffic dots China’s port cities. Ships squeezes through the Panama canals and Suez canals. (An interactive map, created by the data-visualization firm Kiln and University College London’s Energy Institute.)

Iron Will, Iron Road

Only China would seem to have the ability to even consider a project the magnitude of the New Silk Road. Upheavals caused by mega-projects are plagued by detractors in democracies. Transecting an unspoiled wilderness with pipelines or roads in the U.S. may be met with protest from environmentalists. Trying to move villages for a hydroelectric project will cause riots in India. In China, the national will overrides individual and special interests.

But joining the super initiative are 68 countries, all seeking benefits of trade passing through their borders—lands that time and technology may have forgotten can now hope to get into the act.

Not all countries are giving China a green light, however. Regional powers India and Japan (among others) have expressed reservations, each with a historical distrust of China’s international ambition.

What is Happening Right Now?

The New Silk Road is a big story told in billions of dollars.

In Sri Lanka (formerly Ceylon), the financially suffering Hambantota port was handed over to a Chinese company and has received almost $300 million out of a total of $1.1 billion for its revitalization. It has neighboring India a little nervous. A regional power, India has fought wars with Sri Lanka.

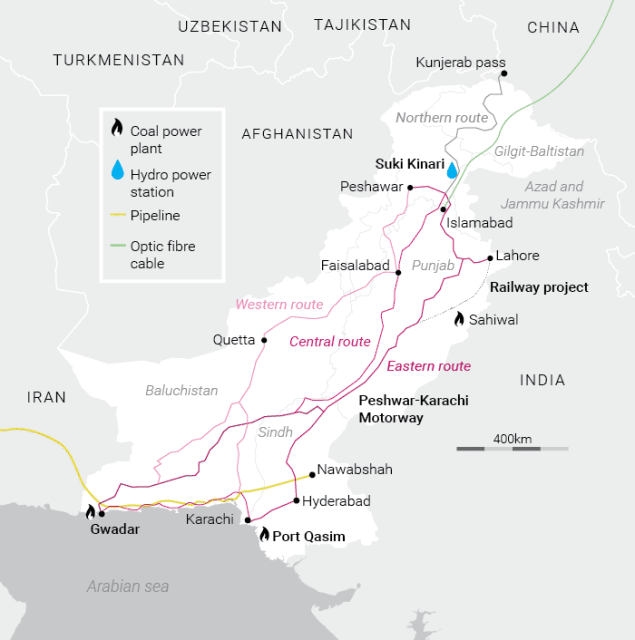

India’s prime minister has loudly objected to roadways cut through regions in dispute with Pakistan. Though these routes from China through Pakistan may not be officially part of the New Silk Road, they might as well be. Pakistan’s old roads will be improved, and new roads will be built. No small task, as the roads will snake over the tallest mountain range in the world with passes of over 5,000 meters. China has promised Pakistan $46 billion in energy and infrastructure—about 1/6 of Pakistan’s GDP. While the roads and rail will shortcut Chinese goods to Karachi and the Gwadar Port (half the cost of the much longer sea route), the coal power plant and hydro power stations planned will benefit the local economy for generations.

An estimated $300 billion has already been spent.

Eastward, Ho.

Tibet, annexed by China in 1951, is known for the Dalai Lama (he used to live there), yaks—and one of the most inhospitable climates in the world. China sees it as a frontier to be settled, much the same way as the US thought of its West in the 1800s. Only 2 million Tibetans occupy an area that is somewhere in size between Texas and Alaska. There are 40 Chinese cities with more people than the entire Tibet Autonomous Region. To balance the population load, a railway was built.

It was a railway they said could never be built and qualifies as one of the modern world’s engineering marvels. Opened with great fanfare in 2006, China invited travel writers seeking the ultimate luxury rail adventure. It wasn’t a luxury. Complaints include not enough oxygen (oxygen masks drop from overhead and the highest elevation is 17,000 ft.) and the vomiting. But the pristine vistas and clear skies may be enticing enough for Chinese fleeing overcrowded cities, rampant pollution and limited opportunity. They may hope to tap into timber and mineral wealth. They will need places to live and an infrastructure to support them.

Gassing up in Russia

China and Russia, “frenemies” through recent history, are acting on the opportunity provided by the void left behind by the U.S. in international relations. The China-Russian deal in 2014 has China buying 38 billion cubic meters of natural gas from Moscow for $400 billion. Parts of the New Silk Road are the pipelines that must be built to handle the flow of gas. In addition, plans call for road and rail to be newly constructed or improved (like the Trans Siberia Railway).

Chinese sources have the New Silk Road snaking through Poland and Germany, ending its western overland route by dropping off containers in London, after use of the existing Chunnel.

China’s trade with European nations is said to be a billion dollars a day and the E.U. trade with China is second only to the US—a situation that could easily switch to China’s favor with the completion of the New Silk Road.

Another country spurned by the U.S is being courted by China and included in New Silk Road projects: Iran. A New Silk Road corridor opened up in 2016 as a freight train completed a 10,000-km journey from Tehran, Iran to China.

Will it Work?

China has spent some of its 5,000 years of civilization in isolation. But since the emergence of a globalized economy, the choice has been either active participation or marginalization as the world passes by. Haltingly at first, Communist-led China has found advantage in participating in capitalist markets with its incredibly large human population. Cheap labor never seems to run out and workers work diligently for more hours per day and more days per week than in the West. Add to that the apparent disregard for costly safeguards Western nations have (arguably) put in place for protection of man and animal, of air and water, and the country has the formula for an engine to be able to make, grow or mine just about everything the rest of the world wears or uses. The New Silk Road is not only an expansion and improvement in the methods to get the goods out there at a faster rate, it creates a further dependence on China and increases its influence.

That’s if it all goes according to plan. China’s economy is deemed slow when GDP dips below 7 percent—when United States and European countries get than 2 percent growth. China’s population growth has been on a decline for decades, which will limit the labor force, if it hasn’t already. The aforementioned work conditions may also cause workers to ultimately throw a collective wrench in the engine. The smog over its cities gets thicker and the rivers have become more toxic; that will not be a cheap clean up, further slowing down the economy. China also has to play nice with others. Neighboring countries may see it as the big kid who has finally come out of his house to play but could steal their marbles. Building trust could be slow. China is also finding out that people in other countries are not as easy to control as its own. Parts of the New Silk Road stop abruptly at some countries’ borders, as their rulers fidget with more pressing issues.

Nevertheless, there is no mistaking such a huge investment will make a big difference when coupled with the force of a unified people and government and a massive investment.

Historians may one day see the New Silk Road as the catalyst for a new world order, with China on top. All without firing a shot.

Source : www.engineering.com